Part 1. Wardley’s Creek to Rothsey

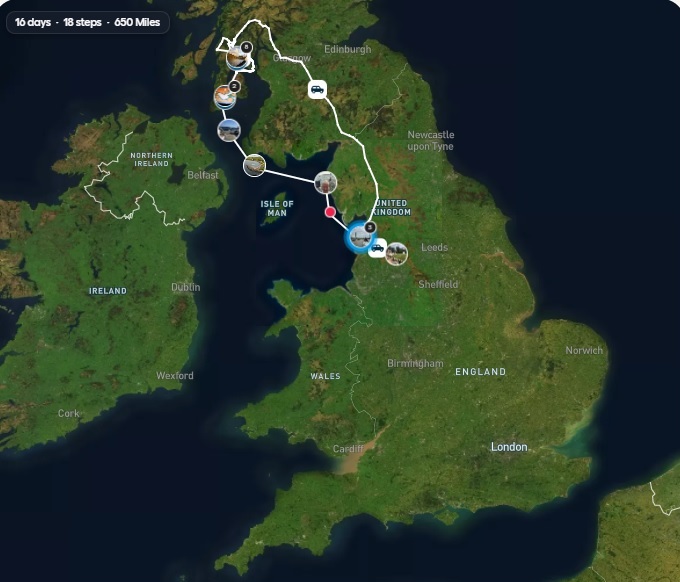

Jamila’s summer cruise took us smoothly across the sparkling Irish Sea. A summer wind pushed us north toward the bonny banks of Scotland. It had been years since I last sailed these waters, and I felt excited about the journey ahead. I knew the two-week trip would be short, but I wanted to take it slow. I aimed to find a nice spot at the journey’s end, where I could enjoy the beautiful landscape before returning in September to bring her back home.

Loading the boat with all the necessary supplies was no easy task. Every item seemed to require its own place, whether it was the gear, tools, or the vital heating charcoal that would keep me warm on cold nights. I had packed an impressive array of provisions—hearty meals, cold beer and gin & tonics, wine, a well-equipped medical kit, and even a few books and games for some downtime. With seven five-litre diesel cans alongside a full main tank, I was ready to untie my moorings. As usual, I struggled with forgetfulness, leaving behind a few important items I had prepared. After giving a farewell wave to some familiar faces on the jetty, I set off on an exceptionally low August spring tide, leaving half an hour early just to be safe—after all, the last thing I wanted was to have my keel stuck in the mud at departure.

The start of the journey was a lengthy motor sail along the beautiful Cumbrian coast, where I stayed close to the shore to fully appreciate my surroundings. I loved the experience, enjoying the views of serene bays, hidden beaches, and charming coastal towns that dotted the landscape. The wind was almost nonexistent, with only gentle cat’s-paws shimmering on the surface of the sea coming from the east. This eased any anxieties I had about anchoring in exposed waters, a necessity that would inevitably arise as the daylight and my energy began to fade. As night fell, I continued sailing for a while, spending a good hour perched on the bow and scanning the darkening waters for the telltale buoys of lobster pots. The distant sparkle of lights from the seaside villages twinkled like stars against the shore.

A sunrise start, Port Logan about a mile behind.

I anchored in the bay of St Bees, and it caught on the first try, holding steady all night. The night was calm and beautiful, and I slept soundly. At 6 a.m., I woke to a quiet scene with little happening around the beach. Thirty years earlier, I had arrived on this beach one morning at the start of Wainwright’s Coast to Coast two-hundred-mile walk.

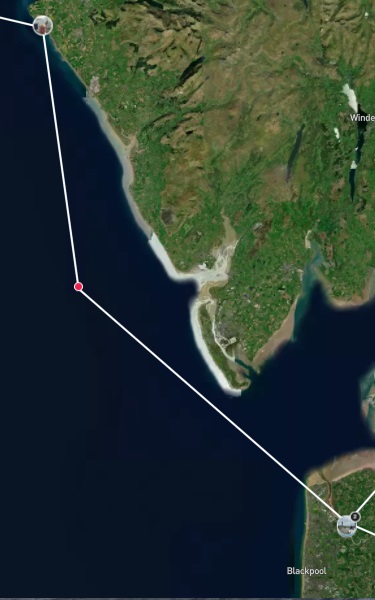

I left St. Bees and headed northwest, passing the Isle of Man on my left and Luce Bay on my right. Before long, the Mull of Galloway appeared on the horizon. With a favourable tide, my boat, Jamila, surged ahead, at times reaching speeds of 8 knots toward the looming cliffs, only to slow to 2 knots due to back eddies. About an hour later, while continuing along the Scottish coast

An hour before dark, I arrived at Port Logan Bay. It was a wide bay with white sands, a welcoming spot that provided good shelter from the easterly wind. Eventually, I found the perfect place to drop anchor.

The perfect spot was close inshore, where I could immerse myself in the vibrant scene unfolding before me. The ‘getting a bit shallow’ at low tide wasn’t a worry as there was little swell, and what wind there was came off the land. My two bilge keels and their bolts would get an easy time!

Small boats bobbed gently on the shimmering water, while colourful canoes and lively inflatables wove in and out among them. Fathers and sons, boyfriends and girlfriends, laughter and chatter filled the air as young couples shared tender moments, capturing memories that would linger in their hearts long after the day ended. The sun sparkled on the water’s surface, adding a magical glow to the atmosphere, making each interaction feel truly special.

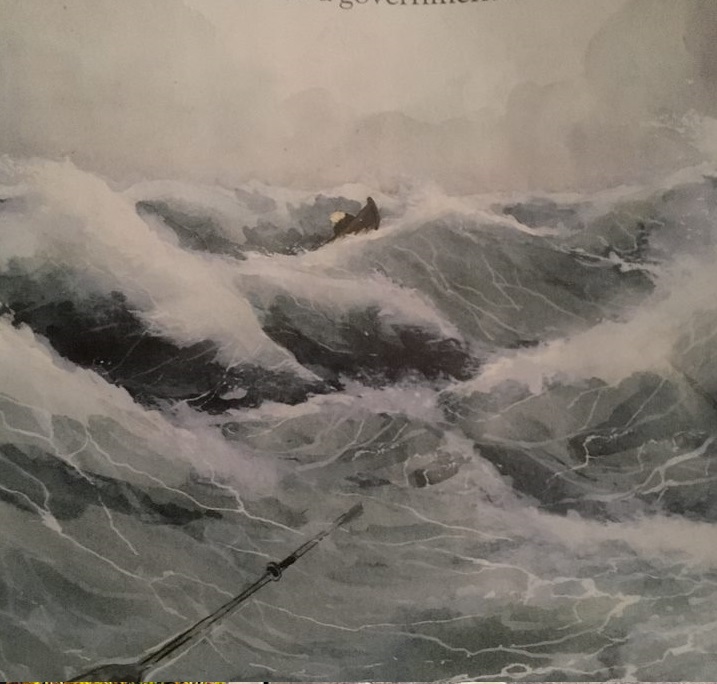

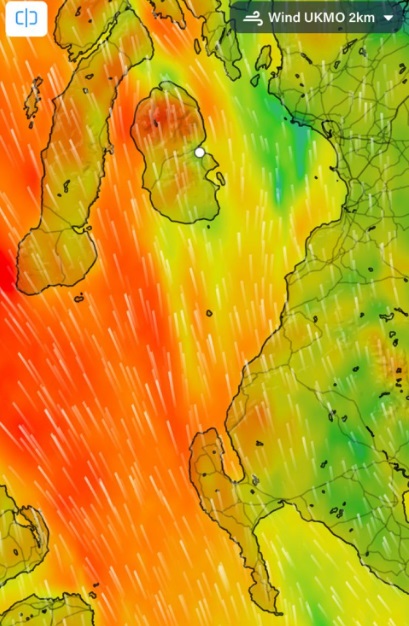

The next leg of the journey was up the North Channel as far as Campbeltown, which is tucked in behind the Mull of Kintyre. A bit of history: during World War II, the North Channel served as the final stage for crucial convoys travelling from the United States, and many sailors felt a palpable sense of elation after surviving the crossing. For Jamila, it was a calm departure from Port Logan. However, as I passed Port Patrick, the wind picked up, and by the time I entered the Firth of Clyde, conditions had changed.

This was the first part of the trip to experience strong winds. Hitherto, the two preceding passages were in light winds, motor sailing to maintain sensible arrival times.

Strong southerly winds, two deep reefs in the mainsail, and enough jib to balance things out.

One of the greatest delights of this passage was the breathtaking view of Ailsa Craig, a striking rocky island that majestically guards the entrance to the Firth of Clyde. This solitary island, adorned with a lush canopy of vibrant trees, evokes an aura more reminiscent of a tropical paradise than its Scottish surroundings. Its rugged cliffs rise dramatically from the dark blue waters, suggesting the whispers of hidden treasures buried somewhere within its mysterious embrace. One can’t help but imagine that this enchanting island holds countless secrets waiting to be discovered.

Campbeltown

After an excessively windy sail down the east side of Kintyre, I was relieved to find myself in the sheltered waters near the large island that guards the entrance. I managed to reach someone on the VHF radio and located the first suitable finger pontoon, where I tied up with the help of another sailor. The sunny blue sky, which had been quite windy, changed overnight. In the morning, Campbeltown appeared gloomy, leaving me feeling down and reluctant to do anything—an anticlimactic moment. However, my spirits lifted when the sun came out later in the day. I was able to buy twenty litres of 30/70 diesel and some other supplies before leaving Campbeltown for a relatively short passage along the west side of Arran to Lochranza.

I enjoyed a remarkable sailing journey down from Campbeltown. Shortly after departing the marina, I hoisted my creamy white sails and swiftly navigated past the imposing island that stands guard at the entrance. The wind, a robust F4/F5 blowing from the southwest, propelled me forward with enthusiasm. As I set my course northward, with the rugged Kintyre peninsula to my port side and the picturesque Isle of Arran to starboard, I found myself with four hours of uninterrupted sailing. This was the perfect opportunity to delve into the settings of my new Tiller Pilot and juxtapose its performance with my less-than-reliable in heavy weather, Simrad autopilot. The results of my comparisons were quite intriguing. I discovered that the Pelagic Tiller Pilot outperforms the Simrad when a firmer hand is required to maintain course; translate: it works whenever. However, the Simrad truly shines when it comes to making lighter adjustments; it appears to have an inherent ability to recognise cyclical movements in the wind and sea. This means it understands when only a gentle nudge is needed to keep the vessel on track, ensuring a smoother, more comfortable ride.

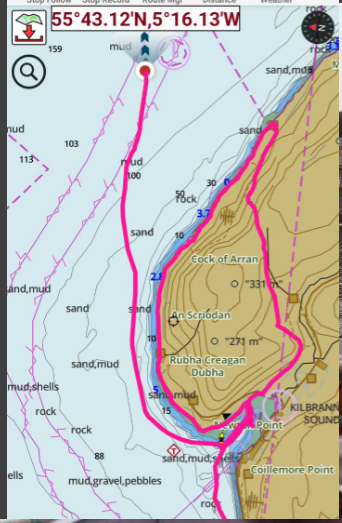

I went ashore and embarked on the scenic Cock of Arran route, which offers stunning views of the coastline. Along my journey, I came across a remarkable geological landmark that holds great historical significance. Nearly 300 years ago, the Scottish geologist James Hutton conducted groundbreaking research here, identifying unconformities in the rock layers that revealed gaps in the geological record. His meticulous observations and analyses led him to propose that the Earth is not merely thousands of years old, as commonly believed based on biblical interpretations, but rather billions of years old. This revolutionary idea challenged the prevailing notions of his time and laid the foundation for modern geology, marking a pivotal moment in our understanding of the planet’s history.

The above image shows my comings and goings, my anchorage and my walk around the ancient rock formations. I came back over the hill, which was extremely challenging, very steep, with thick heather.

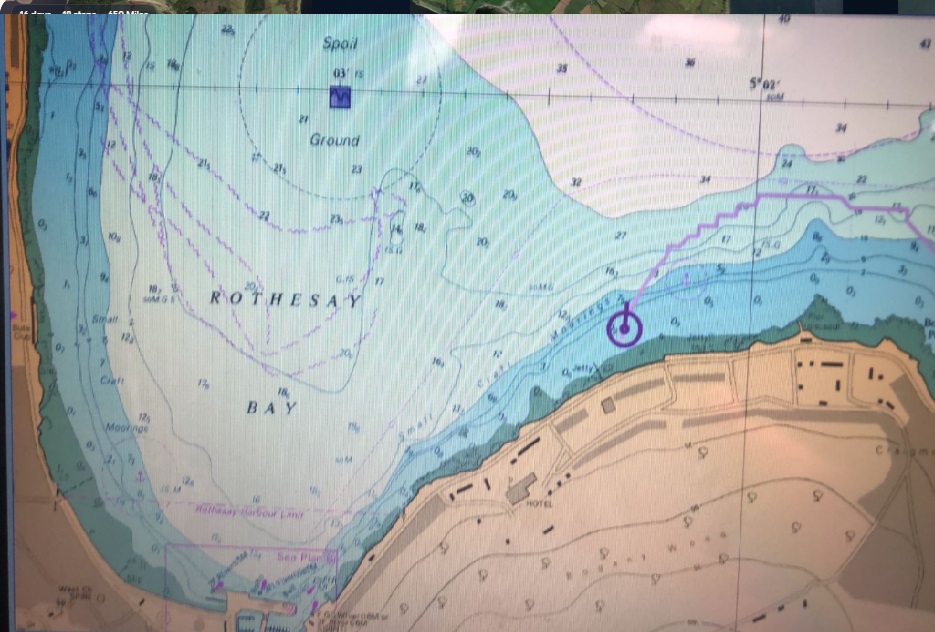

Jamila has an eclectic mix of three chartplotters, eliminating the need for paper charts and traditional RYA coastal skipper navigation skills. The first is a Windows laptop that runs a raster plotter, equipped with all the Admiralty charts for Great Britain. The second is a modern Android smartphone that features vector charts for the Irish Sea and the west coast of Scotland. Additionally, there is an older Garmin plotter from 2012, which is out of sight. All three chartplotters provide accurate positioning within ten meters. Ironically, the software and processors used in billion-dollar satellites orbiting in space are from an older generation.

Rothesay, Kyles of Bute

A wonderful day’s sail to Rothday. To begin with, it was perfect blue sky, blue sea, warm wind with no need for the iron donkey. Clouded over later, but nevertheless felt blessed.

Sailing in awe-inspiring scenery. The weather has been favourable, allowing for a broad reach across the head of the Isle of Arran, followed by four tacks—a couple to starboard and then a couple to port—into Rothesay Bay.

There are many beautifully solid stone houses along the seafront, built by successful Glaswegians during the heyday of the world’s first industrial revolution.

To be continued…